WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Walking alone on a rather well-lit street in the Columbia Heights neighborhood in D.C., I make my way home at around 11 p.m. Headphones in my ears, I’m minding my own business when I pass a young man on a bike. As soon as I make eye contact, I regret it. Please don’t turn around, I will him in my head.

Too late. He turns around and starts following my footsteps. “Hey beautiful” I hear over my music. I’m annoyed, but also scared. Nobody is around. It’s late. My only defense is an almost-dead iPhone.

He eventually left and I got home safe, but I continued to constantly look behind me to see if he, or anyone else was following again. Just a couple of days before this incident, Elliot Rodger went on a killing rampage in California because he wanted retribution for all the girls who had refused him. In his final YouTube video online, he says, “You girls have never been attracted to me. I don't know why you girls aren't attracted to me, but I will punish you all for it.”

Yes, I know that every man who follows me or catcalls or asks for my number isn’t a misogynistic mass murderer or a rapist. But the paranoia is there. When statistics show that 1 in every 6 girls in the U.S. is a victim of rape or attempted rape, how can I walk comfortably alone anywhere without the fear of being assaulted?

And why should I or any other woman be walking with that fear?

Casey Alt, an American who has lived abroad shares an experience she encountered while living in Palestine: “My friend got her hair pulled for blowing a guy off, whom she then punched in the face. He retaliated by driving by later and throwing liquid on her.”

Alt also talked about the night she went to Tahrir Square in Cairo. “I was supposed to wait for my friends in the metro, but it was really crowded so I wanted to wait outside near a restaurant. The stairs out of the metro got bottlenecked and I ended up squished in the center of a throng of men. I started to feel hands all over my body. They were grabbing at my clothes, trying to pull off my shirt-dress, pulling my hijab off and putting hands down my pants. One of my best friends had it a lot worse months before. She was dragged around for hours naked.”

A recent study by Stop Street Harassment, a nonprofit working to end harassment in public spaces, finds that approximately 65 percent of women in the U.S. have been victims of street harassment. Two-thirds of those women said that they feared escalation in those situations. The numbers are even higher in Egypt where a 2013 United Nations report found that 99.3 percent of Egyptian women have experienced some form of sexual harassment. A study done in Pakistan showed 96 percent of girls experienced harassment, 99 percent in Croatia, 93 percent in Turkey, and 43 percent in London. In India, a survey found that 95 percent of women said their mobility was restricted due to the fear of male harassment. In Korea, Japan and China the figures ranged from 50 to 70 percent of harassments occurring on public transportation.

The SSH defines street harassment as “catcalls, sexually explicit comments, sexist remarks, homophobic slurs, groping, leering, stalking, flashing and assault.”

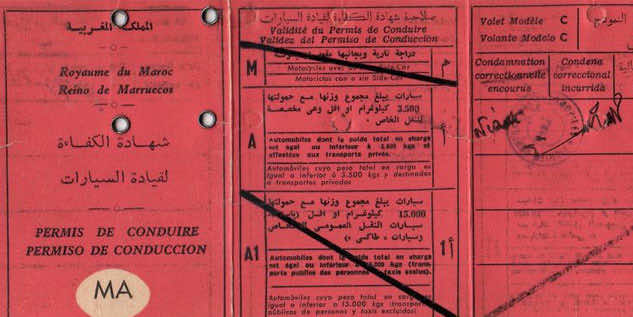

Three years ago, I went on my first study abroad trip to Morocco. I was absolutely shocked at the level of street harassment girls experienced there. We couldn’t walk anywhere without guys catcalling, following us, groping us, or practically-- as we would call it-- “eye raping us.”

I was told by other Moroccans, men and women alike, that this was just “part of the culture.” Many men I talked to didn’t even see this as harassment. In fact, I’ve been told that I should regard it as a compliment.

It is exactly this idea that makes societies and cultures see harassment as a norm. Young boys grow up learning that they are entitled to comment on a woman’s body as if she is a piece of meat.

“There are commercials, print ads, cartoons, TV shows and movies that make light of street harassment, often portraying a stereotypically beautiful woman being verbally harassed by a man. In many cultures, street harassment is not talked about, so these are the only messages kids are receiving about it. Often they internalize that it’s okay and a compliment,” says Holly Kearl, founder of SSH.

A male friend of mine who traveled to Morocco with me says that there needs to be a common understanding among all cultures about women’s rights. “In the East they think the billboards, the Playboy magazines, the way women dress are all violating women. Conversely in the West, many believe that hijabs and niqabs and other forms of covering are curbing women’s rights. Both need to understand that whatever the culture, the woman has the right to decide what she puts on her body and the right to walk out wearing whatever she wants without being subject to harassment.”

Kearl brings street harassment into the broader conversation of women’s equality in society and says that street harassment is simply “one more manifestation” of the inequality in modern society between men and women. We live in a culture where women have less power and respect than men.

It’s not just Morocco or Egypt, but all over the world. And I’ve found that I am always met with the same response by both genders—“Men will be men. Just ignore it.”

And for years that’s what I did -- I ignored the men who followed me in broad daylight, making sexual comments while I pretended not to hear. I ignored the cars that would stop and ask “How much?” if my girl friends and I were standing at a corner alone. Later, in Jordan, I’d hold my head up high and look away from all the leering men, many who would stare and others who would follow and hiss. In India, even when wearing niqab for religious purposes, I’d walk away quickly when I sensed the devouring eyes of men staring as my sisters and I passed by. I didn’t chase the guy who walked up beside me, groped me and ran for it. I ignored it in France, England, Germany and the U.S.

I soon realized, however, that to eradicate street harassment, I couldn’t just pretend it wasn’t happening; I was only enforcing it by not saying anything.

“We will never end street harassment without first talking about it: what it is, how it impacts us and why we need to address it. And we need to end it because it is a human rights violation. It prevents people from having equal access to public spaces and the resources and opportunities there,” Kearl says.

So what can we do to help fight? Women, if you feel safe, assertively respond to harassers. Let them know their actions are unwelcome and wrong. If, however, you don’t feel comfortable talking to them, report the harassment to police or transit workers. To both men and women, if you see someone else being harassed, intervene. Don’t be an enabler.

On a larger scale, we need to bring awareness to our communities and countries. We need our governments to recognize this ongoing struggle women face everyday and help to fight harassment. We need to educate our youth for the future generations so that our daughters can walk on streets and ride on metros without the fear of being assaulted, and so that they can live in a world where men do not objectify them, but rather, see them as equals.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Morocco World News’ editorial policy

© Morocco World News. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, rewritten or redistributed