![Woman Expelled from French Opera House Because of Veil]()

New York - The universality of Islam invalidates the claim that veiling of any kind is mandatory for all Muslim women, and, for that matter, negates the notion of particular clothing requirements for all Muslims. The Quran states “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you into nations and tribes that you may know one another” (49:13). The Quran recognizes and accepts cultural differences. It is hardly a controversial statement that clothing is among the most salient manifestations of culture. (Had God intended uniformity of dress upon embracing Islam, the Quran would have indicated so, but it most definitely does not.)

The majority of Muslims, if not all, firmly believe that the Quran was sent as guidance for all of humanity and view Islam as a universal and timeless religion. Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is likewise considered the final messenger of God for all people, rather than the Prophet of 7th century Arabia or a Prophet sent to the Arab tribes only. The Quran states: “We have not sent thee (Muhammad) but as a mercy to all the nations” (21:107).

Similarly, the equality of all human beings, except in good character and piety, is an undisputed principle of Islam. Prophet Muhammad stated in his last sermon that “All mankind is from Adam and Eve, an Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab…” The language is clear and without room for debate: Islamically, no culture is superior to another.

It is another uncontested fact that women in pre-Islamic Arabia used to veil themselves when going outside their homes; women in several other parts of the world have never observed a similar custom. The Quran was revealed within a specific geographical and historical context and, therefore, its particulars, or its illustrations of principles, refer to the practices common to that society. However, with the spread of Islam, “each new Islamic society must understand the principles intended by the particulars. Those principles are eternal and can be applied in various social contexts.”(1)

In Arabia, before the advent of Islam, the women belonging to rich and powerful tribes “were veiled and secluded as an indication of protection.” It is important to emphasize that the veil was not an Islamic innovation; it was in use for generations before the birth of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).The Quran, instructing modesty as a principle, illustrated it with the practices that were common at the time. However, the Quran’s mandate is the general principle of modesty, rather than veiling and seclusion, which are cultural manifestations that pertain to a specific context.

Otherwise, how could it be true that Islam is universal and timeless, all humans and cultures equal under it, none superior to another, yet simultaneously true that all women, irrespective of the time and place they exist in, who accept Islam as their faith, should proceed to adopt the dress mores of 7th century Arabia? This is entirely absurd and not Islamic but rather cultural. The particular display of modesty of 7th century Arabia is not the only “right” one or the one superior to all others.

The way modesty was expressed before and during the lifetime of the Prophet is quite different from how it is manifested in other societies. Because Islam is a religion for all times, it logically does not follow that despite the religion’s universality and timelessness, Muslim women all over the world must continue to show their modesty and piety in 1400 year old Arab standards. Moreover, “Allah intends for [us] ease and does not intend for [us] hardship” (2:185).

The notion of a veiling requirement for women is based on a fundamental error of interpretation: that of confusing the general principles of Islam with their particular illustrations and it is very damaging to the religion and to the overall progress of Muslims. This style of interpretation turns Islam into a “rigid canonical religion geared towards…external matters” and makes Muslims appear to be “confusing content and form, aim and method, spirituality and ritual.”(2)

This stubborn fixation on women’s “proper Islamic attire” strips Islam of its true nature of depth and empowering wisdom.

There is no dispute about the importance of modesty or about the fact that modesty is required and central to Islam for both men and women. But claiming that modesty demands, for instance, that a Muslim woman living in New York City in 2014, wear garb that originated, was useful in, and symbolized modesty and dignity in the desert of Arabia 1400 years ago is completely ridiculous. No person, male or female, living in a modern society, let’s say, contemporary America, Europe or Asia (and even many parts of North Africa and the Middle East), would consider a woman showing her hair to be immodest. Neither are men these days particularly provoked by the sight of a woman’s hair.

Among today’s morally questionable fashions and cultural practices, a woman’s uncovered hair is hardly a temptation or a show of moral laxity. But, let’s imagine that it were in fact a ‘temptation’. Let’s pretend present-day men were somehow so weak as to be provoked by glancing a woman’s hair, still, the solution is within themselves. Modesty is also required of, and was first mandated to, men: they are ordered to lower their gaze, purify their thoughts and dress modestly too. The answer is not for women to make it their central preoccupation to ensure by all means that they do not cause men any impure thoughts. This is, again, absurd: Islam teaches that in the eyes of God, each person is responsible for his or her own actions.

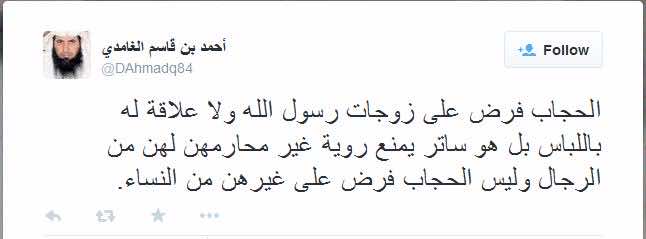

So, where do the veiling notions come from? There are three Quranic verses that deal with the issue of hijab which are commonly known as “ayat al hijab”:

The first of these verses deals exclusively with the household of the Prophet and is not to be extrapolated to other people. In this particular context the Quran orders that “whenever you ask them (the Prophet’s wives) for anything, ask them from behind a curtain (hijab)” (33:53). The reason for this revelation is simple:

“In Madinah, the need had arisen to protect the household of the Prophet, who had now become head of State, from easy informal access by each and everyone. This was done separating the official and the private quarters which has since become routine in official residence. This division was achieved with the aid of a screen (hijab).”

It is a major tragedy that this verse has been misinterpreted to the point of requiring women in certain countries to never leave their screened-off quarters even while out in the street. During the time of the Prophet, women were free to move around in society, encouraged to learn, invited and welcome to Islamic gatherings where they sat among men and used to pray in the mosque side by side with men. The practices of secluding women are actually un-Islamic.

The other two verses that discuss women’s dress code have a general application:

“O Prophet! Tell your wives and your daughters as well as all believing women that they should draw over themselves some of their outer garments (min jalabibihinna); this will help to assure that they are recognized (as decent women) and not be annoyed” (33:59).

It is of utmost importance to note that this rule does not require women to wear a specific type of clothing, such as a large headscarf, and then pull it over the breast. “The Quran assumes that women wear an article of clothing that allows the covering of their breasts, and that this is done. In ancient times, this article would have naturally been worn over the head in hot, windy, dusty countries. However, a Quranic requirement for this cannot be derived from 33:59.” (3)

The final clothing regulation that appears in the Quran discusses the protective purpose of these rules: “And tell the believing women to lower their gaze and guard their private parts and not to display their charms beyond what may decently be apparent thereof. So let them draw their head coverings (which were commonly worn at the time, not implemented) over their bossoms” (24:31).

The first two injunctions of not staring at the opposite sex in a provocative manner and hiding one’s primary sexual parts are also imposed on men with the same wording (Quran 24:30). The third rule, displaying those charms that are normally visible (ma zahara minha), “is a very sensible regulation: It takes into account that from period to period and from culture to culture there are great differences in the view of what, aside from her genitals and breasts, is erotic about a woman.”

Murad Hoffman, in his book, Islam: The Alternative, cites a rector of the Great Mosque in Paris, Sheikh Tedjini Haddam, as explaining that what Islam actually recommends is that “a woman be decently dressed.” And the application of this recommendation varies depending on the social environment.

Dr. Sultan Abdulhameed perfectly explains this idea in The Quran and the Life of Excellence:

“In order to benefit from spiritual teachings, it is important to separate the essential from the peripheral. We should recognize the principle of progressive change in religious as well as in cultural and social life. Truth is eternal, but the way it is expressed changes with time, and it is experienced differently by different people.”

*It is important to note that I am not opposing or criticizing a woman’s decision to cover her hair or to dress in a particular way for a wide variety of reasons, such as announcing her moral values through her attire, expressing her disagreement with the increasing pressure (at least in the West) for women to be scantily dressed or perhaps, for identity reasons, including preserving one’s cultural identity or externally communicating one’s religion to society. However, the idea that all Muslim women are required by Islam to veil themselves (in any form) is false and damaging to women, to Islam and to people who might otherwise consider accepting Islam as their faith.

_________________

1- Wadud, Amina. Quran and Woman. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. 9. Print.

2- Hoffman, Murad. Islam the Alternative. Maryland: Amana Publications, 1997. 133. Print

3- Hoffman, Murad, id. p. 131

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Morocco World News’ editorial policy

© Morocco World News. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, rewritten or redistributed